CRISPR is a big deal. Its promise is great, but it also brings risks and raises critical issues that warrant public discussion.

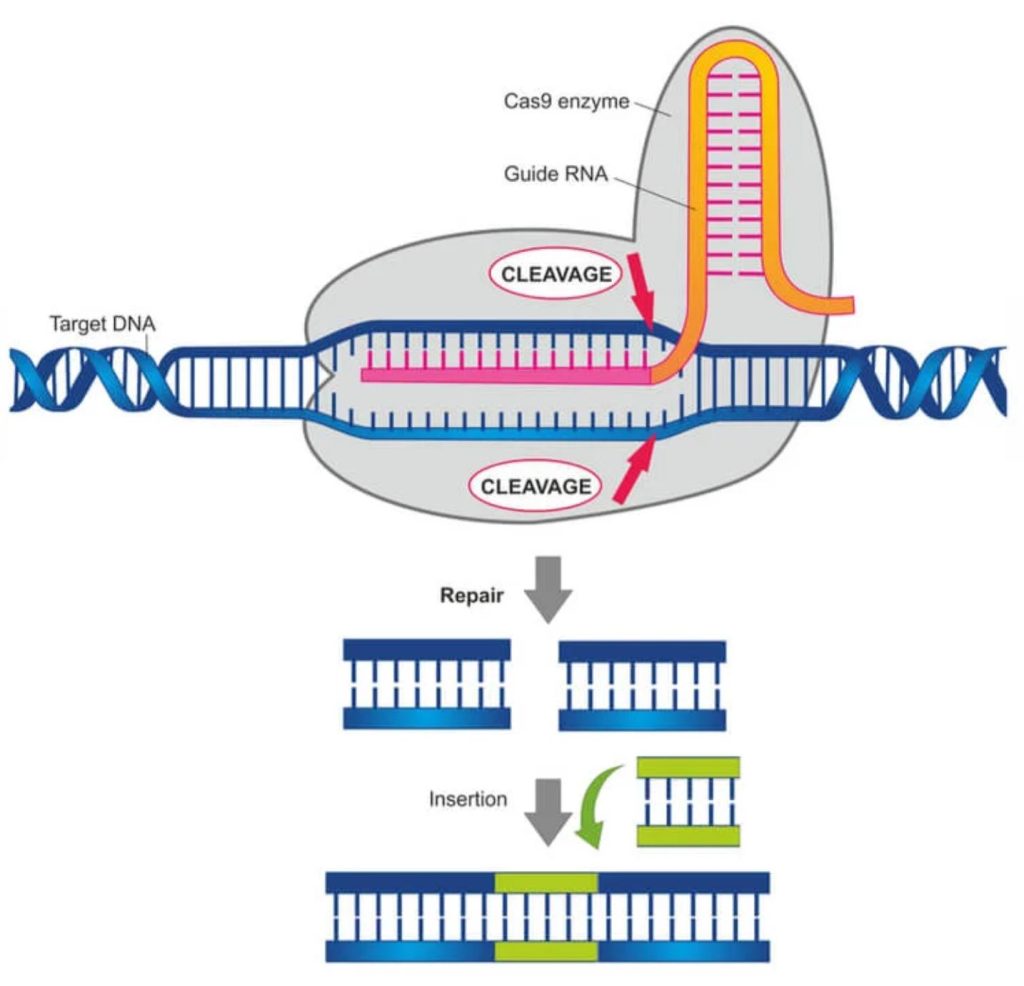

This powerful technique offers a relatively easy way to precisely edit the genetic code by “cutting and pasting.” Custom RNA is used to guide an enzyme (Cas9) to a specific section of DNA, where base pairs can then get deleted, replaced, or added. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the underlying research to Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, the first time women were the sole recipients. (The acronym CRISPR [pronounced “crisper”] stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.)

The applicability of CRISPR-based genetic engineering is broad, ranging from bacteria to human cells. For example, it has the potential to make crops more resilient against effects of climate change, to eliminate disease-carrying insects, and to treat or even cure diseases such as cancers.

CRISPR has already been used in clinical trials to treat the bone marrow stem cells of patients with sickle cell anemia, “correcting” the point mutation that causes red blood cells to take a painful sickle shape. This type of gene editing is non-inheritable because the change is made to somatic rather than reproductive cells. However, CRISPR can also be applied to so-called germ cells, which form sperm and eggs, and to embryos. These edits can be inherited, raising the stakes since the genetic changes will be passed on to future generations.

Although the promise of CRISPR is great, its use raises many issues. Like other technologies, genomic editing is a double-edged sword. Despite assuming positive intentions, its use may lead to unintended consequences and result in undesirable outcomes. For example, it was only after wide application of DDT that its harmful environmental impact became apparent.

CRISPR, like previous less powerful genetic engineering techniques, also raises ethical issues. One is affordability, since it is likely to be expensive, at least initially. Use primarily by wealthy nations and individuals would further inequity and the social divide between those who afford access and those who cannot. Another is whether it should be used to enhance desirable human physical and cognitive abilities. That raises the specter of eugenics, which sought to improve the human race by eliminating “defective” genes.

The application of CRISPR technologies invites many questions. How to ensure that new therapies reach those who most need them? What risks can be tolerated to achieve the desired benefits? What genes can be modified and who gets to decide? And should editing human germ cells or embryos be permitted at all? How and by whom should its use be regulated? Public engagement and debate is critical to resolving these and other challenges.

A step in that direction has been taken by the National Informal STEM Education (NISE) Network. In 2018, as part of its Building with Biology project, they created for implementation at 20 sites a “Should We Edit the Genome” public forum kit that was subsequently made available online (link below). NISE Net was originally funded by NSF in 2005 with $20 million to foster public engagement through exhibits and programs on nanoscale science and technology, which were then emerging. A similar large-scale national project focused on CRISPR-associated technologies and the issues they raise is needed now.

Although relatively uncommon due to the corporate sources of much exhibition funding, addressing the dual nature of technology is not new. Some 40 years ago, NEH-funded “Technology: Chance or Choice?” at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry highlighted both the benefits and risks of key technologies from the previous 50 years at the time. An early version of the personal computer (Texas Instruments 99!) presented visitors with three quotes for each: one favorable, one opposed, and one neutral. After thinking about, discussing, and entering their selection, they were able to see how previous visitors had responded.

Related Articles

Ucko, D. A. (1983). “Technology: Chance or choice?”- A museum exhibit on the impact of technology. Science, Technology, and Human Values, 8(3), 47-50. doi: 10.1177%2F016224398300800308

Ucko, D. A. (2017). Preface. In L. Bell & V. Olney, Leading and managing the NISE Network: Practical solutions for creating a flexible national network (pp. 9-10). NISE Network.

Resources

iBiology & Youreka Science. CRISPR: A word processor for editing the genome.

NISE Net. “Should We Edit the Genome?” Forum.